Sites often use HTTP or URL parameters to redirect users to a specified URL without any user action. While this behavior can be useful, it can also cause open redirects.

Mechanisms

For example, when these users visit their account dashboards at https://example.com/dashboard, the application might redirect them to the login page at https://example.com/login.

Therefore, the site uses some sort of redirect URL parameter appended to the URL to keep track of the user’s original location.

For example, the URL https://example.com/login?redirect=https://example.com/dashboard will redirect to the user’s dashboard, located at https://example.com/dashboard, after login.

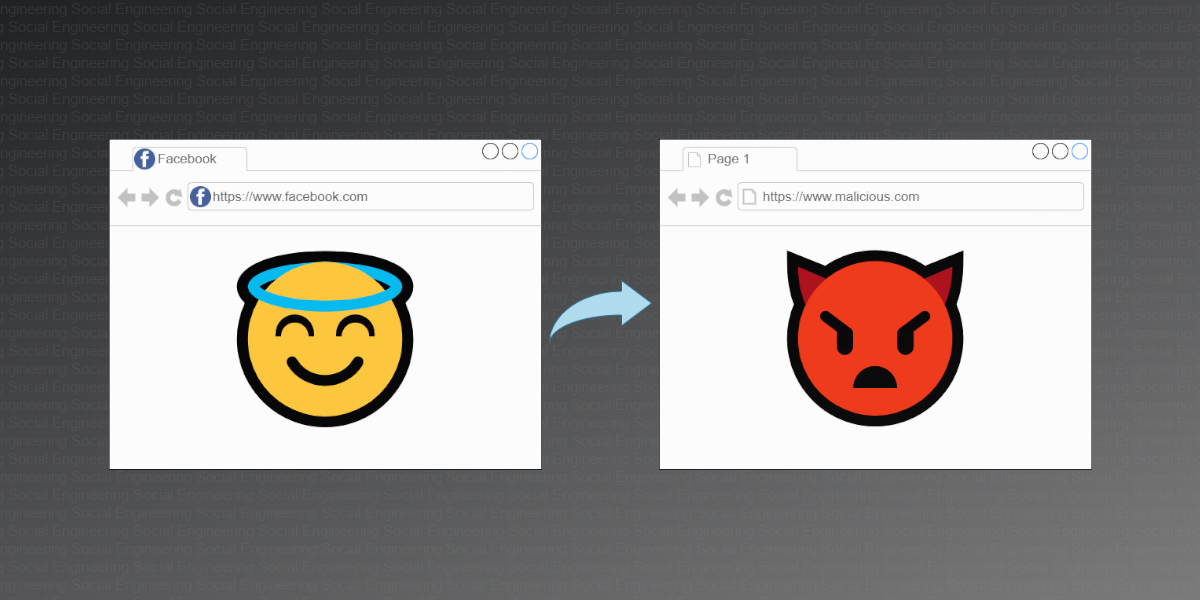

During an open-redirect attack, an attacker tricks the user into visiting an external site by providing them with a URL from a legitimate site that redirects somewhere else, like this: https://example.com/login?redirect=https://attacker.com.

Another common open-redirect technique is referer-based open redirect.

The referer is an HTTP request header that browsers automatically include. It tells the server where the request originated from. It’s a common way to determine the user’s location come to form.

Thus, some sites will redirect to the page’s referrer URL automatically after certain user actions, like login or logout.

<html>

<a href="<https://example.com/login>">Click here to log in to example.com</a>

</html>

When a user clicks the link, they’ll be redirected to the location specified by the href attribute of the tag, which is https://example.com/login in this example.

If example.com uses a referer-based redirect system, the user’s browser would redirect to the attacker’s site after the user visits example.com, because the browser visited example.com via the attacker’s page.

—

Hunting for Open Redirects

You can find open redirects by using a few recon tricks to discover vulnerable endpoints and confirm the open redirect manually.

Step 1: Look for Redirect Parameters

These often show up as URL parameters like here:

<https://example.com/login?redirect=https://example.com/dashboard>

<https://example.com/login?redir=https://example.com/dashboard>

<https://example.com/login?next=https://example.com/dashboard>

<https://example.com/login?next=/dashboard>

Open your proxy while you browse the website. Then, in your HTTP history, look for any parameter that contains absolute or relative URLs.

An absolute URL is complete and contains all the components necessary to locate the resource it points to, like https://example.com/login.

Some redirect URLs will even omit the first slash (/) character of the relative URL, as in https://example.com/login?next=dashboard.

Note that not all redirect parameters may have straightforward names like redirect or redir.

I’ve seen redirect parameters named RelayState, next, u, n, and forward. You should record all parameters that seem to be used for redirect, regardless of their parameter names.

These pages are candidates for referer-based open redirects.

To find these pages, you can keep an eye out for 3XX response codes like 301 and 302.

These response codes indicate a redirect.

—

Step 2: Use Google Dorks to Find Additional Redirect Parameters

Start by setting your site in the URL : site:example.com

Then look for pages that contain URLs in their URL parameters, making use of %3D, the URL encoded version of ( = )

The following searches for URL parameters that contain absolute URLs: inurl:%3Dhttp site:example.com

This search term might find the following pages:

https://example.com/login?next=https://example.com/dashboardhttps://example.com/login?u=http://example.com/settings

Also try using %2F, the URL-encoded version of the slash /. The following search term searches URLs that contain =/, and therefore returns URL parameters that contain relative URLs:

inurl:%3D%2F site:example.com

This search term will find URLs such as this one: https://example.com/login?n=/dashboard

Alternatively, you can search for the names of common URL redirect parameters.

inurl:redir site:example.com

inurl:redirect site:example.com

inurl:redirecturi site:example.com

inurl:redirect_uri site:example.com

inurl:redirecturl site:example.com

inurl:redirect_uri site:example.com

inurl:return site:example.com

inurl:returnurl site:example.com

inurl:relaystate site:example.com

inurl:forward site:example.com

inurl:forwardurl site:example.com

inurl:forward_url site:example.com

inurl:url site:example.com

inurl:uri site:example.com

inurl:dest site:example.com

inurl:destination site:example.com

inurl:next site:example.com

These search terms will find URLs such as the following:

<https://example.com/logout?dest=/>

<https://example.com/login?RelayState=https://example.com/home>

<https://example.com/logout?forward=home>

<https://example.com/login?return=home/settings>

—

Step 3: Test for Parameter-Based Open Redirects

Insert a random hostname, or a hostname you own, into the redirect parameters; then see if the site

automatically redirects to the site you specified:

<https://example.com/login?n=http://google.com>

<https://example.com/login?n=http://attacker.com>

Some sites will redirect to the destination site immediately after you visit the URL, without any user interaction.

But for a lot of pages, the redirect won’t happen until after a user action, like registration, login, or logout. In those cases, be sure to carry out the required user interactions before checking for the redirect.

—

Step 4: Test for Referer-Based Open Redirects

Finally, test for referer-based open redirects on any pages you found in step 1 that redirected users despite not containing a redirect URL parameter.

To test for these, set up a page on a domain you own and host this HTML page:

<html>

<a href="<https://example.com/login>">Click on this link!</a>

</html>

Replace the linked URL with the target page.

Then reload and visit your HTML page.

Click the link and see if you get redirected to your site automatically or after the required user interactions.

—

Bypassing Open-Redirect Protection

Here, you can see the components of a URL. The way the browser redirects the user depends on how the browser differentiates between these components:

scheme://userinfo@hostname:port/path?query#fragment

For example, how would the browser redirect this URL?

<https://user>:password:8080/example.com@attacker.com

In this case, you could try to bypass the protection by using a few strategies, which I’ll go over in this section.

Using Browser Autocorrect

Modern browsers often autocorrect URLs that don’t have the correct components, in order to correct mangled URLs caused by user typos.

For example, Chrome will interpret all of these URLs as pointing to https://attacker.com/ :

https:attacker.com

https;attacker.com

https:\\/\\/attacker.com

https:/\\/\\attacker.com

These quirks can help you bypass URL validation based on a blocklist.

For example, if the validator rejects any redirect URL that contains the strings HTTPS:// or HTTP://, you can use an alternative string, like HTTPS; , to achieve the same results.

Most modern browsers also automatically correct backslashes () to forward slashes (/), meaning they’ll treat these URLs as the same:

https:\\\\example.com

<https://example.com>

If the validator doesn’t recognize this behavior, the inconsistency could lead to bugs. For example, the following URL is potentially problematic:

https://attacker.com\@example.com/

But if the browser autocorrects the backslash to a forward slash, it will redirect the user to attacker.com, and treat @example. com as the path portion of the URL, forming the following valid URL:

https://attacker.com/@example.com

—

Exploiting Flawed Validator Logic

For example, as a common defense against open redirects, the URL validator often checks if the redirect

URL starts with, contains, or ends with the site’s domain name.

You can bypass this type of protection by creating a subdomain or directory with the target’s domain name:

<https://example.com/login?redir=http://example.com.attacker.com>

<https://example.com/login?redir=http://attacker.com/example.com>

However, it’s possible to construct a URL that satisfies both of these rules. Take a look at this one:

<https://example.com/login?redir=https://example.com.attacker.com/example.com>

Or you could use the at symbol (@) to make the first example.com the username portion of the URL:

<https://example.com/login?redir=https://example.com@attacker.com/example.com>

—

Using Data URLs

You can also manipulate the scheme portion of the URL to fool the validator.

data:MEDIA_TYPE[;base64],DATA

For example, you can send a plaintext message with the data scheme like this: data:text/plain,hello!

For example, this is the base64-encoded version of the preceding message: data:text/plain;base64,aGVsbG8h

For example, this URL will redirect to example.com:

data:text/html;base64,PHNjcmlwdD5sb2NhdGlvbj0iaHR0cHM6Ly9leGFtcGxlLmNvbSI8L3NjcmlwdD4=

## encoded from <script>location="<https://example.com>"</script>

You can insert this data URL into the redirection parameter to bypass blocklists:

<https://example.com/login?redir=data:text/html;base64>,

PHNjcmlwdD5sb2NhdGlvbj0iaHR0cHM6Ly9leGFtcGxlLmNvbSI8L3NjcmlwdD4=

—

Exploiting URL Decoding

URL encoding converts a character into a percentage sign, followed by two hex digits; for example, %2f. This is the URL-encoded version of the slash character (/).

When validators validate URLs, or when browsers redirect users, they have to first find out what is contained in the URL by decoding any characters that are URL encoded.

Double Encoding

For example, you could URL-encode the slash character in https://example.com/@attacker.com. Here is the URL with a URL-encoded slash:

https://example.com%2F@attacker.com

And here is the URL with a double-URL-encoded slash:

[https://example.com%252f@attacker.com](https://example.com%252f@attacker.com/)

Finally, here is the URL with a triple-URL-encoded slash:

[https://example.com%25252f@attacker.com](https://example.com%25252f@attacker.com/)

For example, some validators might decode these URLs completely, then assume the URL redirects to example.com, since @attacker.com is in the path portion of the URL.

However, the browsers might decode the URL incompletely, and instead, treat example.com%25252f as the username portion of the URL.

On the other hand, if the validator doesn’t double-decode URLs, but the browser does, you can use a payload like this one:

https://attacker.com%252f@example.com

The validator would see example.com as the hostname. But the browser

would redirect to attacker.com, because @example.com becomes the path portion of the URL, like this:

https://attacker.com/@example.com

—

Combining Exploit Techniques

To defeat more-sophisticated URL validators, combine multiple strategies to bypass layered defenses. I’ve found the following payload to be useful:

<https://example.com%252f@attacker.com/example.com>

Most browsers will interpret example.com%252f as the username portion of the URL.

But if the validator over decades the URL, it will confuse example.com as the hostname portion:

https://example.com/@attacker.com/example.com

—

Escalating the Attack

For example, they could send this URL in an email to a user:

https://example.com/login?next=https://attacker.com/fake_login.html.

Though this URL would first lead users to the legitimate website, it would redirect them to the attacker’s site after login.

But open redirects can often serve as a part of a bug chain to achieve a bigger impact.

For example, an open redirect can help you bypass URL blocklists and allowlists. Take this URL, for example:

https://example.com/?next=https://attacker.com/

This URL will pass even well-implemented URL validators because the URL is technically still on a legitimate website.

You could also use open redirects to steal credentials and OAuth tokens.

Often, when a page redirects to another site, browsers will include the originating URL as a referer HTTP request header.

When the originating URL contains sensitive information, like authentication tokens, attackers can induce an open redirect to steal the tokens via the referer header.

—

Finding Your First Open Redirect!

You’re ready to find your first open redirect. Follow the steps covered in this chapter to test your target applications:

- Search for redirect URL parameters. These might be vulnerable to

parameter-based open redirects.

- Search for pages that perform

referer-based redirects.

- Test the pages and parameters you’ve found for open redirects.

- If the server blocks the open redirect, try the protection bypass techniques mentioned in this chapter.

- Brainstorm ways of using the open redirect in your other bug chains!

—

Prevention

For example, a site may blocklist knew malicious hostnames or special URL characters often used in open-redirect attacks.

When a validator implements an allowlist, it will check the hostname portion of the URL to make sure that it matches a predetermined list of allowed hosts.

If the hostname portion of the URL matches an allowed hostname, the redirect goes through.

Otherwise, the server blocks the redirect.